1. A sunset

I wanted to write about a sunset.

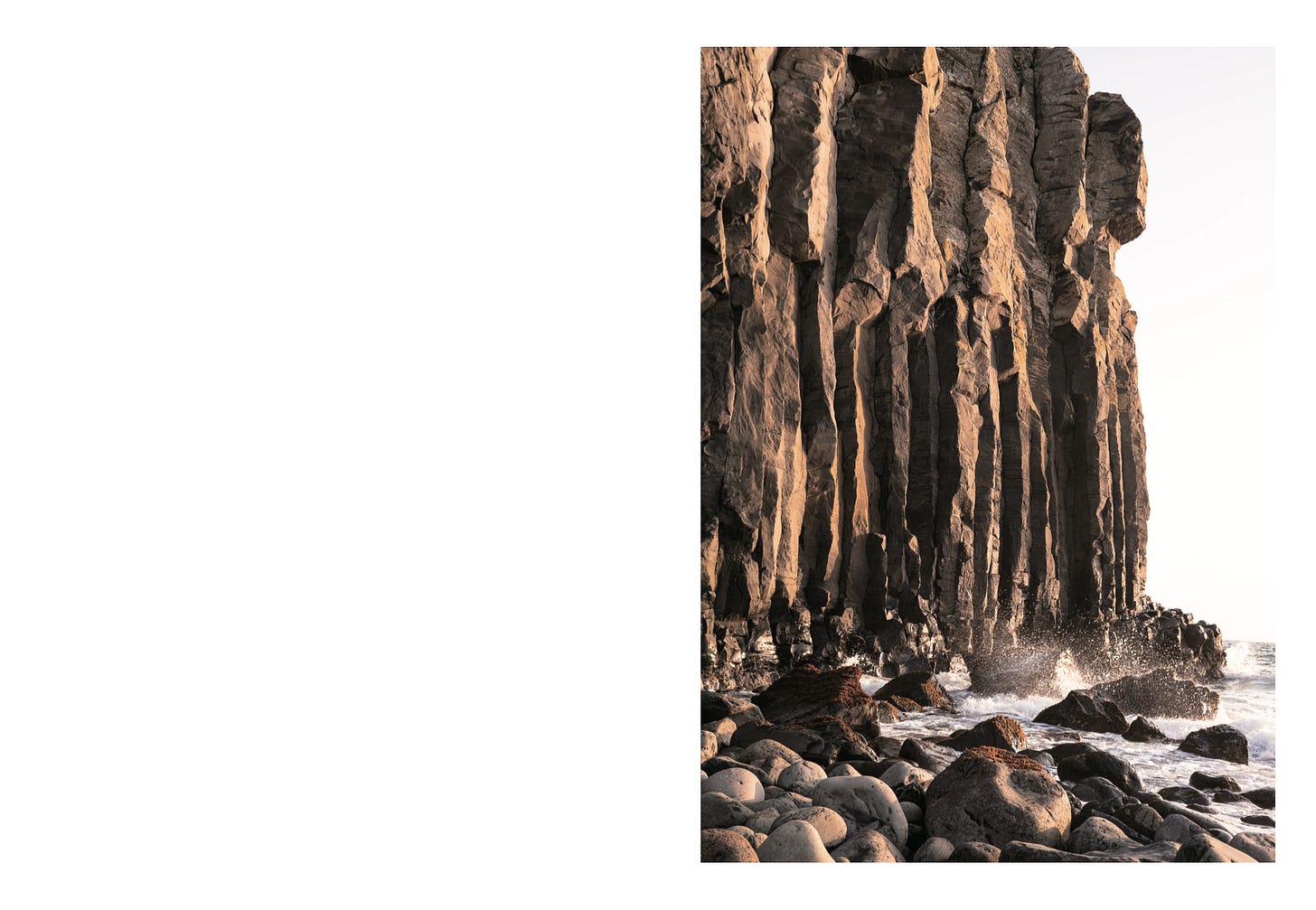

It wasn’t just any sunset, though. It was a sunset in Lombok, Indonesia, orange-lacquered gold glittering against the Indian Ocean. and I wasn’t just sitting on the beach somewhere: I was in the water, my happy place, catching wave after wave as the sun rested her head against the jagged peaks of Gili Wayang behind us.

And I wasn’t there alone. Somewhere on the beach sat Taty, a friend I had met at my hostel the day before, a stranger at the breakfast table that had gradually — and still, quickly — turned into a friend as we crossed the island together on the back of my motorbike. As I paddled over each set, a part of me felt reassured by the knowledge of her presence, waiting for me on the shore. And a part of me wondered, too, at how you can get to know someone over the course of a day, sketch the outlines of a stranger, paint the color between the lines of that first impression from the moment their existence intertwines with yours.

I wanted to write about this sunset, and I rewrote the section over and over again, turning words like slipstreams and building paragraphs up only to deconstruct, rearrange, and destroy them again. I did this because for me the memory of that evening deserved more than just prose. It wasn’t just a memory: it was an atmosphere, an irreality, a dreamstate that wove together every thread of my senses and thought and mindscape. I wanted to capture it in all its rawness, beauty, and uncertainty. Words alone didn’t seem to suffice.

On my fifth rewrite I finally sat back and asked myself: what if I wasn’t just writing with words?

What if there were other ways I could capture, and convey, this moment?

2. Why my story needed more than prose

My year of backpacking was lived in colors, textures, and silences; my memories of it chronicled across photographs and journals alike. I traveled as a photographer: two cameras in my backpack at all times, one digital, one film. I traveled, too, as an archivist — an archivist of my mind. In the midst of one of the most introspective, transformative periods of my life, I filled notebook after notebook with loose thoughts, questions, and reflections from a 25-year-old boy who had left everything behind to chase a dream. Images and words: these were the languages I wielded to make sense of this odyssey of mine.

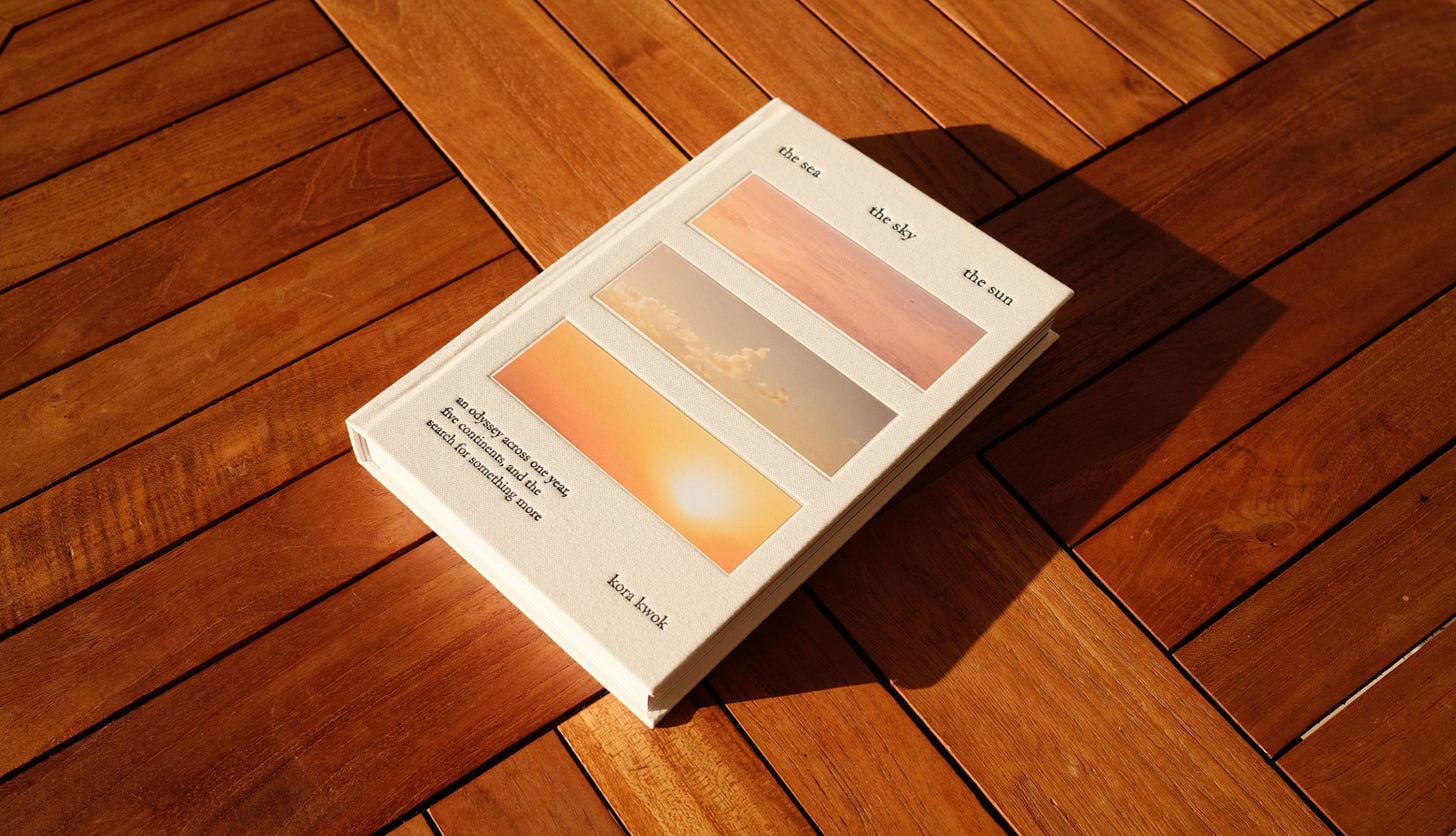

As I began writing the book that would become the sea, the sky, the sun, I realized I already had a treasure trove of archival memories I could weave into the memoir. I had hundreds and hundreds of images from the road, views and vignettes across five continents, burned into SD cards and rolls of 35mm film. I had my journals, too, which brought a direct look at the inner turbulence of my mind.

In writing, there’s a familiar rule-of-thumb: show, not tell. Instead of stating what’s happening — “it was sunset,” for example — writers try to evoke the scene through details: the way light glitters on the water, the golden wash of evening against the palms.

I wanted to take this idea further in my memoir. I didn’t want to simply explain, or even just show. I wanted my readers to feel. I could write paragraphs attempting to describe the vivid melancholy of staring out at the ocean in the middle of heartbreak, and how, in that very same moment, the evening sun carried a sense of hope and wonder about the world, a quiet reassurance that everything would be okay.

Or I could let other forms of storytelling bear some of that weight instead.

In my art practice, I’ve always been drawn to installation and sculpture — a concrete monolith built into the mountains of New Mexico, an immersive installation that sought to recreate the sight, sound, and smell of the sea. I’m drawn to these mediums because I believe their multi-dimensional, multi-sensory nature makes them incredibly effective vessels of meaning and emotion. It wasn’t until I began creating the sea, the sky, the sun that I finally understood what I had always felt through my art. Showing is better than telling, that we already know. But to immerse someone, to allow them to be, to feel, is a million times more powerful than that.

3. What is a visual memoir?

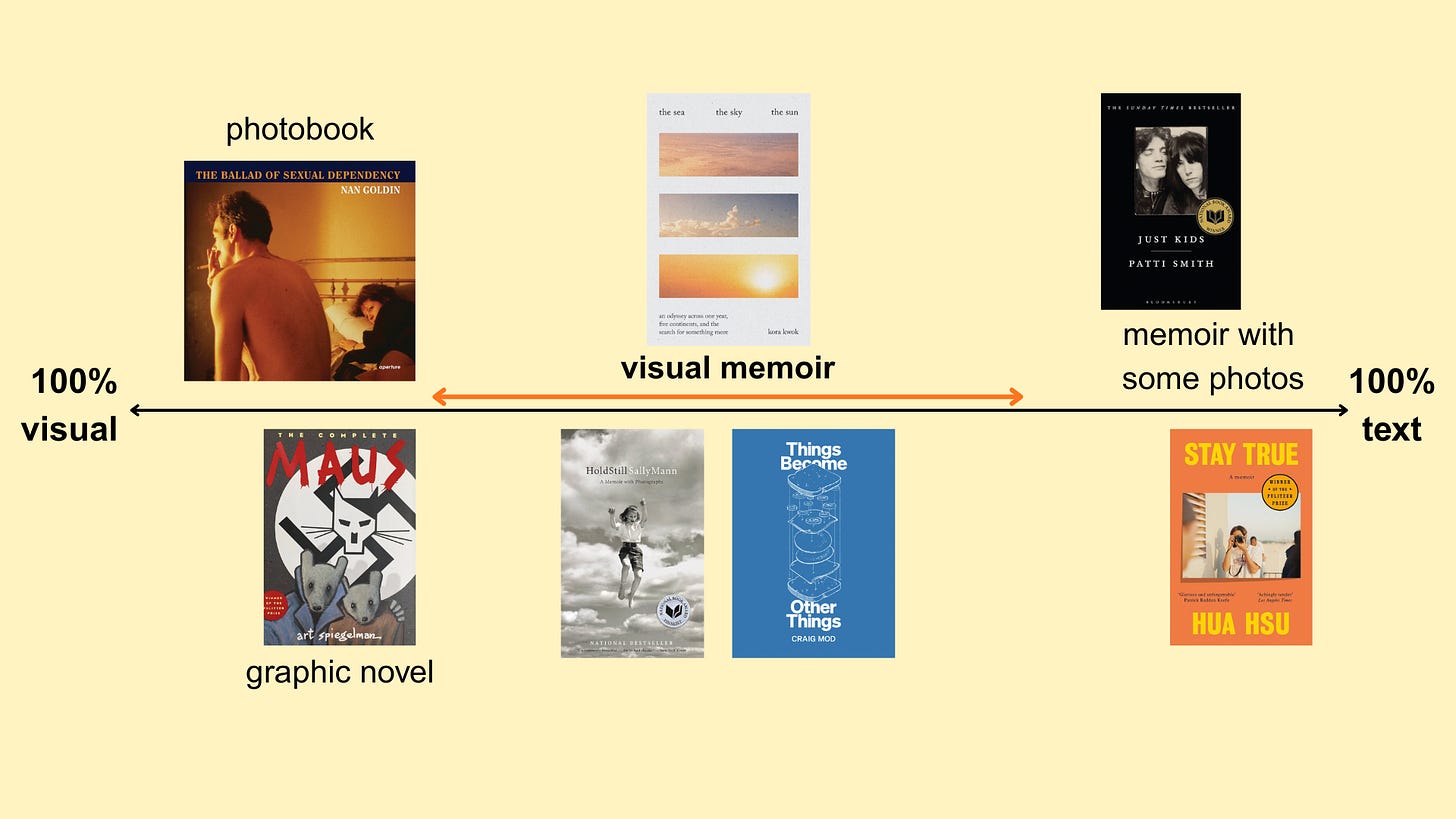

A visual memoir is a personal story told through words and images. It strikes a fine balance between the two elements: it’s not a photobook or graphic novel; nor is it a traditional memoir with a few sparse images interspersed throughout. It’s a format where visuals and text share narrative authority — where visual images are as essential to meaning as words, and where the reader’s understanding of the story relies on the interplay of the two.

The visual memoir often requires the author to embody both the skills of a writer and visual artist. For this reason, it’s not a common medium, and mostly written by writer-photographers. The first example that comes to mind is Sally Mann’s Hold Sill (2015), which weaves the author’s photographs into a memoir on her life as an artist and mother. Another example is Craig Mod, who similarly weaves photography into Things Become Other Things (2023), a “walking memoir” through Japan and his past.

There’s a fine line between visual memoir and “memoir with some photos.” Patti Smith’s Just Kids sprinkles a polaroid across every few chapters, but does that make it a visual memoir? I would argue not: those images feel more like a supplement to the text, rather than a fellow narrative authority. The book could stand on Smith’s (incredible) prose alone.

If I had to put a number on it, I’d say a visual memoir is anywhere from 25-65% “visual.” the sea, the sky, the sun balances 80 pages of photography and journal fragments between 220 pages of prose. Craig Mod’s Things Become Other Things has 56 photographs in 220 pages of text. But it ultimately comes down to the feel of the book as a whole and not numbers alone.

4. Building a visual rhythm

the sea, the sky, the sun isn’t just a memoir interspersed with photographs and journal fragments. It’s a book where blank pages give readers space to breathe, where photographs speak what prose could not, and where journal fragments offer a glimpse into my mindscape and thoughts.

As I formed each chapter, I asked myself: were there any places where an image or journal entry could speak louder than prose? Where could I convey my story more effectively through other forms?

Visual languages are deeply intuitive, and it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly why I chose each image and its placement. But I can highlight a few recurring ways I used photographs throughout the memoir:

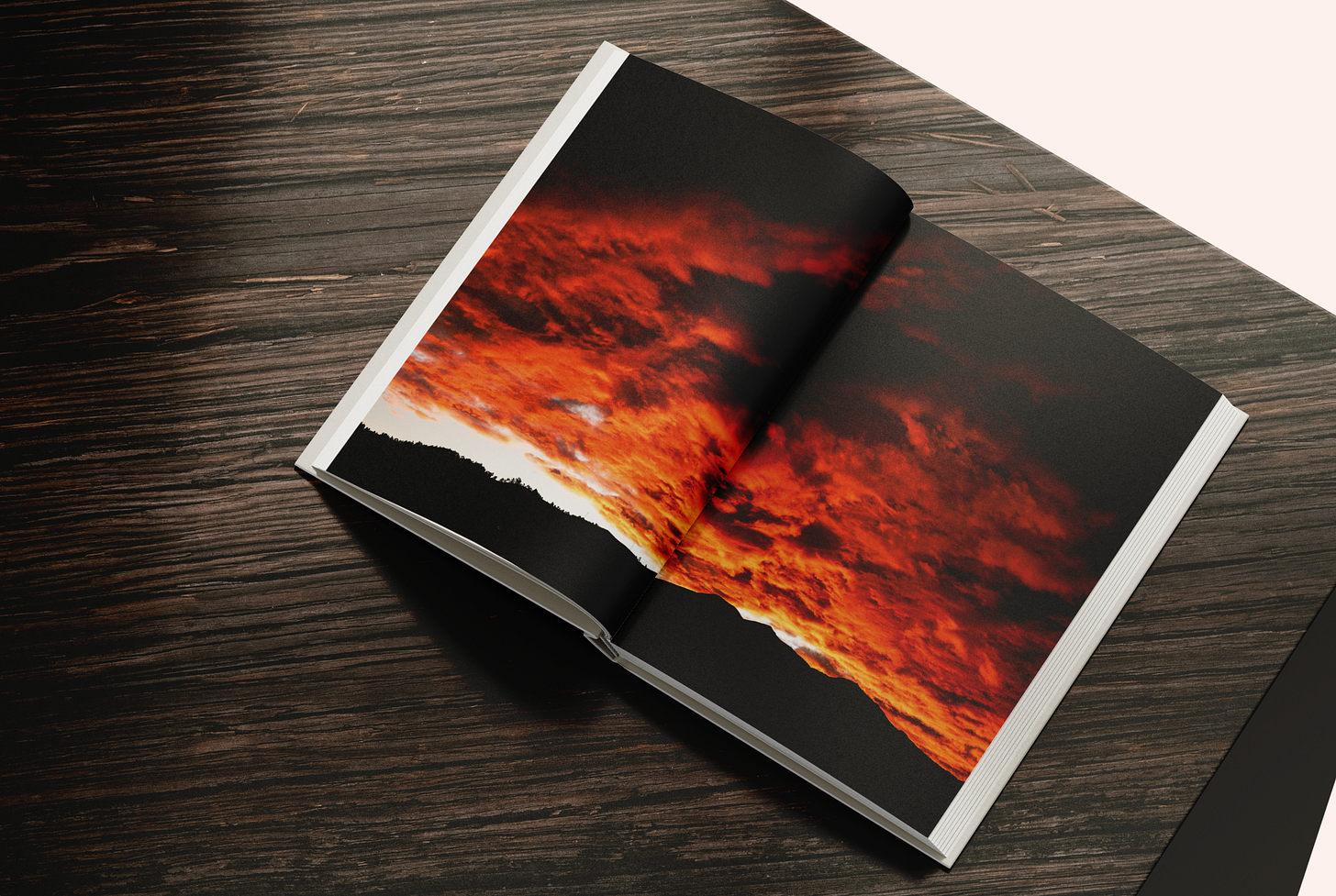

Capturing an atmosphere or emotion: a dash of sunflowers after a reflection on love. Stormwaters crashing against a cliff to illustrate an inner turbulence. A purple-red sunset in the midst of hurt.

Setting the mood through color tones: cooler, muted tones to show melancholy and introspection. Brightly lit, warm-toned photos in times of joy and exhilaration.

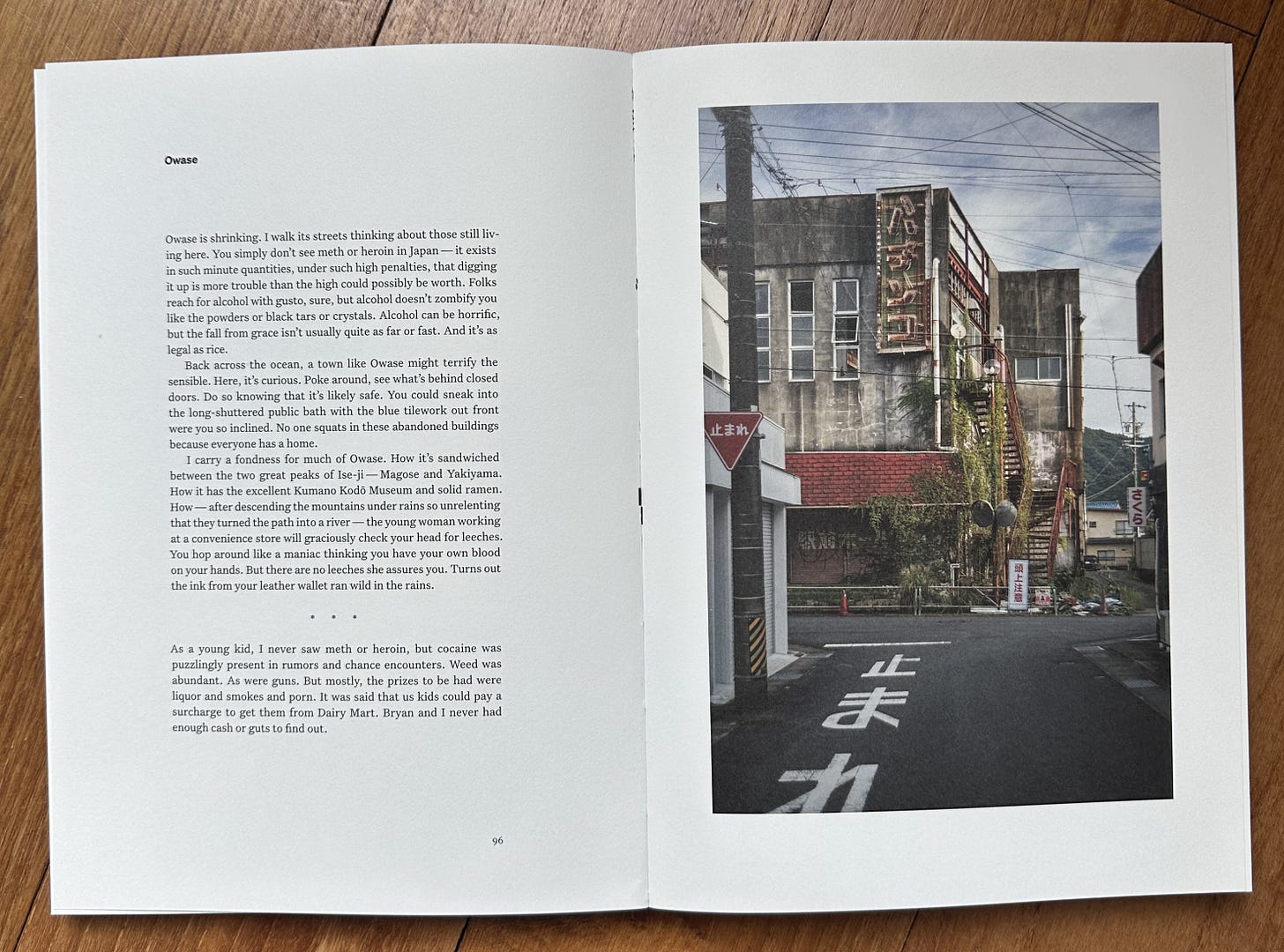

Supplementing themes discussed in text: in the Japan chapter, I discussed the country’s dueling natures of tradition and subversion, order and chaos — and paired the text with a series of side-by-side images illustrating these dualities.

Showcasing people and places: portraits of travelers and locals, landscapes that reflected the vistas I experienced.

Creating space and rhythm: full-bleed double-spreads where a single image captured the vastness and beauty of what I witnessed. Blank pages as a natural buffer that gave readers room to pause and breathe.

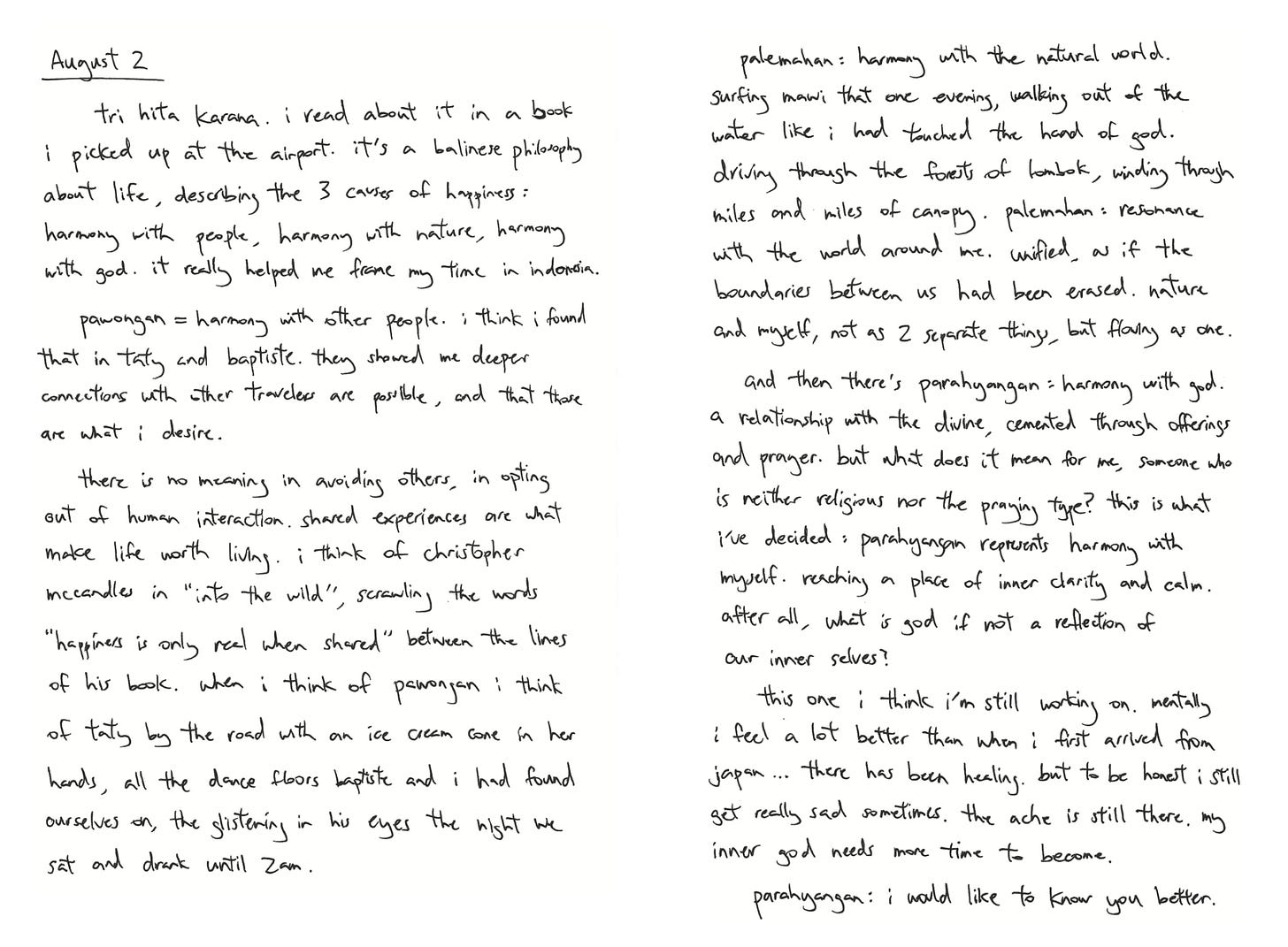

The journal fragments operated a little differently. They provided raw, unfiltered glimpses into my thoughts, often taking the shape of reflections that showed how I felt at that very moment in time. Other times, they allowed space for half-formed ideas or stories that didn’t quite fit into the book’s narrative, but still mattered: humorous moments from the road, or musings on life and happiness.

5. The visual memoir is a medium that demands to be experienced

Ultimately, the visual memoir is a medium that unfolds in multiple dimensions. It demands to be experienced. To write one requires a careful interplay of text, image, and space — and that, in turn, requires returning to the work again and again, reading every chapter and every sequence from start to finish. In doing so, the importance of visual rhythm becomes clear: the pacing created by images, fragments, and empty space working together to carry the story forward.

This is what I hope readers feel when they open the sea, the sky, the sun. It’s not just a story to be read, but a space to move through.

If this post intrigued you, the sea, the sky, the sun is available for purchase here. I’ll continue sharing more about my writing process and inspirations in upcoming posts.

👋 If you’d like to support my book journey, feel free to…

1. Like, share, and restack this post. Any engagement really does help :)

2. Follow my journey on Instagram @kunstlerroaming.

3. Order your copy of the sea, the sky, the sun ♥